By David Yamaguchi,

The North American Post

Pamela Okano’s review of “Bridge to the Sun,” by Bruce Henderson (napost.com, Jan. 13), made the closing point that a title has been lacking from the US history bookshelf. There is nothing on the role of US Army Military Intelligence Service (MIS) Nisei linguists in the Occupation of Japan (1945-1952).

Photo DY

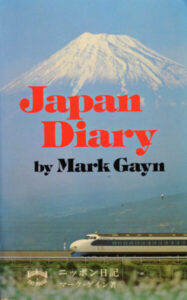

By chance, soon after reading Okano’s essay, I was perusing the Japan bookshelf at Half Price Books and happened on “Japan Diary” by Mark Gayn. It records the daily thoughts of an American journalist who was on the ground in Japan during December 1945 to December 1946. It is a title which I had never come across before, probably because it has long been out of print. First published in 1948, and later reprinted in 1981 and 1989, physical copies of it are rare today. However, as the good-condition paperback that was on the shelf was $40, I put it back that day.

But my doing so later bugged me. So a week later, I returned to purchase “Japan Diary.” While not a Nisei linguist diary, it would paint the general scene of the Occupation, about which I have long been interested, owing to the influential role of linguist Hachiro Kita on my life (napost.com, Jan. 2023).

As I began to read, I will say that few books have caught my attention so swiftly. My first evening, tired after a long day, I read only the first daily entry, before setting it down to sleep. But Gayn had me by page 2.

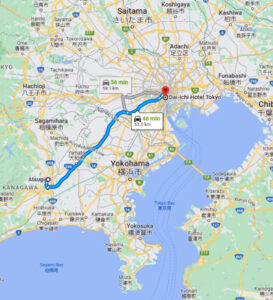

“Dec. 5 TOKYO — We landed at Atsugi… Later, we drove along a narrow and twisting road to Tokyo. The countryside looked well enough — men working in the fields, children playing, radishes drying in the sun…

“But the closer we came to Yokohama, the plainer became the gravity of Japan’s hurt. Before us, as far as we could see, lay miles of rubble. The people looked ragged and distraught. They dug into the debris, to clear spaces for new shacks. They pushed and dragged carts piled high with brick and lumber. But so vast was the destruction that all this effort seemed unproductive… The skeletons of railway cars and locomotives remained untouched on the tracks. Streetcars stood where the flames had caught up with them, twisting the metal, snapping the wires overhead, and bending the supporting iron poles as if they were made of wax. Gutted buses and automobiles lay abandoned by the roadside. This was all a man-made desert, ugly and desolate and hazy in the dust that rose from the crushed brick and mortar.

There was plenty of traffic, but all of it was American and military…”

“Dec. 14… I have known all along that Japan’s rice harvest this season was poor. I did not know how poor until I talked to Major W. H. Leonard this morning. Leonard is a trained agronomist from the Middle West, slow and cautious.

“How bad?” he said. “I’ll tell you how bad. Last week, Kyoto was down to 3.3 days’ supply of food. Tokyo was down to four days’ supply. We figure we’ll get along through February. But March 15 is our danger point. After we reach it, we can expect rice riots. Our troops might be jeopardized…

On page 48, I found what I had been looking for.

“Dec. 21… At eleven, Berrigan and I, with our new interpreter, George Kimura, drive out to Ueno Station, pick our way gingerly among the thousands of passengers sleeping, or waiting their turn for train space which may not come for days, and boarded a night train for Sendai…”

Bottom line: “Japan Diary” places us on the scene. From it, we begin to understand how miraculous it is that Japan emerged from its ruins to become a successful, first-world democracy.

Notes. Japan was hungry because the U.S. torpedoed, mined and bombed its transportation infrastructure and because many of its men had been killed or were still away. While Kimura’s name is lacking from the appendix of MIS veterans listed by Henderson, a “George I. Kimura” is listed as graduating from the Fort Snelling MIS Language School, Minnesota, May 1945 (discovernikkei.org). “Japan Diary” is available on Kindle ($8). That format would be apt as it is straight text, without illustrations.