By Shokichi Tokita For The North American Post

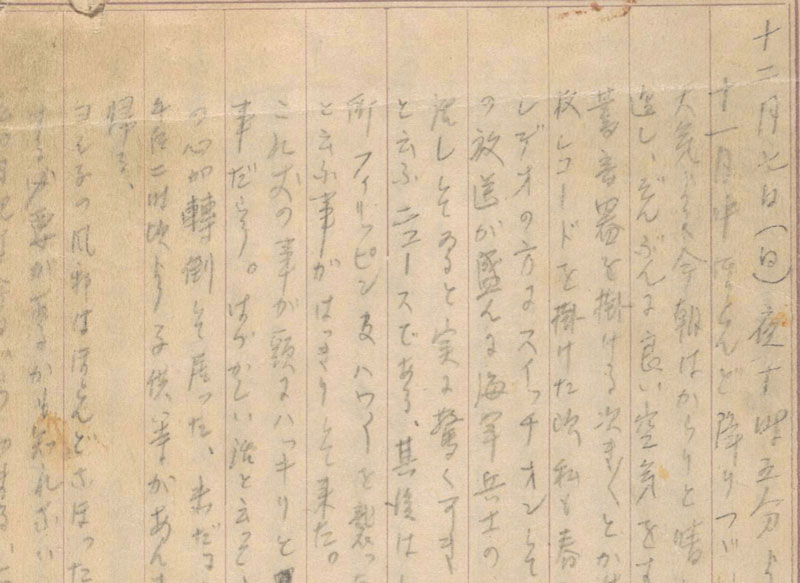

One of the most interesting aspects of the book, “Signs of Home,” which elaborates on my father Kamekichi Tokita’s art history and accomplishments, is that it draws heavily from his diary written during World War II. The diary is quite detailed in his thoughts, fears, feelings of disparity, how it affects him physically, and most of all, his disbelief. It is one of very few writings by an Issei that has been translated into English and into book form.

Yet, what has not previously been described is the meandering path by which my father’s narrative became a book at all. To begin with, the project was started by my Japan cousins, not by Kamekichi’s American family, which would have been the most logical start. The quirks and twists the process encountered along the way are numerous and interesting. Let me explain.

In 1990, Barbara Johns, PhD, who was working for the Seattle Art Museum, contacted me with a suggestion or offer to assist in donating Kamekichi’s notes, sketches and other articles of art, but not his actual art, to the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. Since my wife Elsie and I had been struggling with how to preserve Kamekichi’s various items and art memorabilia, it was, to state it mildly, an offer from heaven! So, without hesitation, we sorted what could be donated including two (of three) volumes of the diary with help from Barbara Johns.

Sometime later, in a visit with my Japan cousin, Kakuko Imoto, a question about what Kamekichi had done in America came up during a discussion about his art work. The fact that much of it was donated to the Smithsonian was stated and Elsie explained how to view it using a computer. When Kakuko collaborated with another Japan cousin, Yasuko Norizuki, to review Kamekichi’s materials, they came across the written diary’s two volumes of page images. Since Kakuko already had the first volume that Mom (Haruko) had given the Japan Tokita family in 1950, she recognized it for what it was and proceeded to download the balance of the diary from the Smithsonian.

After downloading it, they found that the written Japanese was in prewar Japanese with over 10,000 kanji characters; so they gave it to Haruo Takasugi, their brother-in-law, who was sister Tomiko’s husband. He was a retired newspaper editor and was tasked to translate the diary into modern Japanese. (After WWII, Japanese was standardized to about 2,000 characters, deleting those that were rarely used and other variants which made such older material illegible to those educated post-war, except specialists.) Details about his experience working with the old Japanese and converting it to modern Japanese is described in the final book’s appendix.

Once the diary was converted to readable modern Japanese, the document was formally given to me. As I am unable to read written Japanese, I began to search for someone who could translate it to English. Interestingly enough, the task proved to be quite simple, because my (then) daughter-in-law, Karen, knew of a translator in her hometown of Los Angeles. The translator, Naomi Kusunoki-Martin, a Japan-born professional translator was contacted and arrangements were made.

Once translated to English, the next step was to reformat the diary into book form suitable for publication. My nephew, Eric Hwang, started this process by including photos and additional information, transforming it into a more readable and interesting form. The final result was a book manuscript entitled “Conflict of Loyalties.”

Now that the diary was supposedly in book form, an interested publisher was sought. A number of leads were followed, but nothing substantial was accomplished until another fortunate circumstance came about. My son Kurt had a friend whose husband, Michael Burnap, was a member of the board of directors for University of Washington Press. Burnap reviewed it and found it interesting enough to pass it on to UW Press.

UW Press, after reviewing the manuscript, decided that Kamekichi’s background as an artist would be the central theme, rather than just the diary. A meeting was held with its director, Pat Soden, to discuss publishing the book. During the meeting, I was asked if I knew of a possible author who would be able to write about Kamekichi’s life as an artist. At that time, I had just read Barbara Johns’ “East and West,” published by UW Press, about artist Paul Horiuchi’s artistic endeavors. Additionally, knowing Barbara from the time Kamekichi’s memorabilia was donated to the Smithsonian and impressed with her book on Horiuchi, I naturally recommended her!

And so the book “Signs of Home” authored by Barbara Johns, was published by UW Press and introduced to the public at an opening art exhibit at the Seattle Asian Art Museum in October 2011.

As you can see, the final publication of the book involved people and fortuitous circumstances that no one could have foreseen.

In closing, the third (first) volume of the diary was returned to the American Tokita family, who in turn, donated it to the Smithsonian so that all three volumes of the original diary written by my father are now in the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.