History of Seattle Nikkei Immigrants from ‘The North American Times’

This series explores the history of the pre-war Japanese community in Seattle, by reviewing articles in “The North American Times,” which have been digitally archived by the University of Washington and Hokubei Hochi Foundation (hokubeihochi.org/digital-archive). Publication of this series is a joint project with discovernikkei.org.

By Ikuo Shinmasu

Translation by Mina Otsuka For The North American Post

‘The North American Times’ was first printed on September 1, 1902, by publisher Kiyoshi Kumamoto from Kagoshima, Kyushu. At its peak, it had a daily circulation of about 9,000 copies, with correspondents in Spokane, Vancouver BC, Portland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Tokyo. When World War II started, Sumio Arima, the publisher at the time, was arrested by the FBI. The paper was discontinued on March 14, 1942, when the incarceration of Japanese American families began. After the war, the paper was revived as “The North American Post.”

Part 8 Picture-Bride Marriages on the Rise

The last chapter reviewed the history of the Japanese hotel industry in Seattle recorded in “The North American Times” (“Part 7 Flourishing Japanese Hotel Businesses,” napost.com, Aug. 2022). In this chapter, I will introduce articles from 1918 to about 1920 on picture-bride marriages which peaked around 1910.

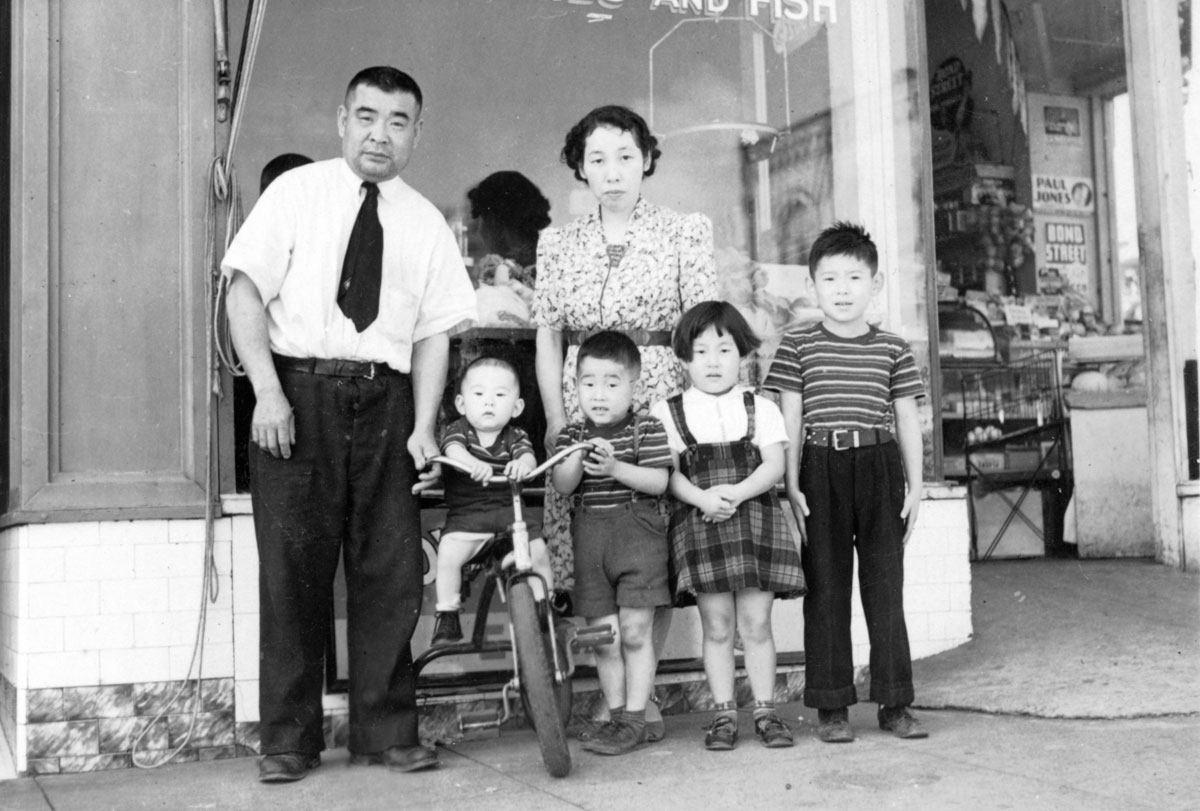

Beginning about 1900, the anti-Japanese movement in America began to get intense. In response, the Japanese government concluded the Gentlemen’s Agreement with the U.S. in 1908. This agreement imposed restrictions on Japanese immigration to America. Since it also made it difficult for Japanese workers in America to return temporarily to Japan, the number of “picture brides” — those that got married through the exchange of pictures without first meeting the other party — increased rapidly. Many Nisei were born as a result of these arranged marriages.

On Picture-Bride Marriages

Akatonbo Nakamura discusses picture-bride marriages in the column “The Rise and Fall of Main Street” (“The North American Times,” Jan. 1, 1939):

“The year 1907 became the last year of Japanese immigration to the U.S. This is because the Gentlemen’s Agreement was enforced as of July 1 of that year. Following its enforcement, picture marriages were still possible. The Smith Cove Terminal witnessed both tragic and comedic scenes in various situations, as ships carried brides one after another, beginning in 1908.

Brides filling the ship gathered at the departure desk and looked at the crowd on the wharf, checking small pictures in their pockets, all seemingly at the same time. As for the grooms who had come to the wharf to welcome their brides, they also looked in their pockets, searching for their matches among the crowd of brides on the deck. This scene gave me such a sentiment which I could not quite explain. Some fainted as they faced each other and some grooms ran away the moment they recognized their brides, leaving the brides, who had crossed the 4,000-mile route of waves, alone there…. The brides arriving in America became a turning point for single men whose work life developed into the so-called family life, leading them to settle down.”

“What Is a Picture Bride?” Picture Marriages from the Caucasian Perspective”

(NAT, July 31, 1919)

“One newspaper in the U.S. asks what a picture bride is and gives its own definition. I’d like to explain how such marriage was perceived by foreigners, just for reference. The words “Japanese picture bride” are quite ordinary on their own, but few people know what the process is like. This is how it’s done.

When a Japanese man in Seattle wishes to marry a woman in Japan but does not intend to go back to Japan himself, he will entrust the marriage to someone else. For example, he will ask his friend, who is in Japan, to complete the marriage documents with her on his behalf. Once they get ‘married,’ they will attach a picture of the bride to her passport. Immigration officers in Japan will then check this and let the bride board the ship. On her arrival in Seattle, she will be detained at the immigration bureau and passed onto her husband, who has committed to the marriage. Very few Japanese women enter the country in other ways. While the immigration bureau wants to prevent more Asian immigrants from entering regardless of gender, there is nothing they can do because of the institution of picture brides.”

Arguments For and Against Picture Marriage

As picture marriage was “approved” by the Gentlemen’s Agreement, the number of picture brides increased rapidly in the 1910s. People had many different opinions, both arguing for and against it.

“Tourist Parties and Brides”

(NAT, May 9, 1919)

The North American Times published an excerpt of an article from a local paper in Hiroshima, “Geibi Nichinichi Shimbun,” to introduce how the marriage of single men in America was perceived in Japan.

“Immigration to America is no longer possible. Today there are about 150,000 Japanese residents in America, engaged in businesses such as agriculture, growing fruits, fisheries, laundry, logging, and some other work mostly in western cities in the U.S. Only about 4500 to 4600 Japanese women have migrated to the U.S.; so one in ten men has a Japanese wife, leaving many unmarried. Since there is a slight chance of finding happiness in marriages with American women, many would visit Japan in the form of tourist groups during winter, when they are less busy with work, with their true purpose being to find spouses. One leader of a tourist group who went to Japan this year said that the group members looked for spouses in places where people have positive views on immigration such as Hiroshima, Okayama, Yamaguchi and Wakayama, and most of them did find wives. From the women’s side, they decided to go because they were divorced or past marriageable age. Some made the decision out of vanity, as they heard about others in neighboring villages who had moved to America sending money to their parents every month or had built a storehouse (“kura,” a traditional fireproof stone house next door to one’s wooden residence, used for storing valuables).

Some might do it because they don’t want to marry in Japan, where they have to deal with a mother-in-law or sister-in-law. There are some, though this is very rare, who wish to gain skills such as machine embroidery. Seventy to 80 percent of them have some “problem.” Because it costs a lot to prepare for marriage in Japan these days, some parents accept the proposals from the U.S. where they won’t be required to get Japanese (traditional) attire ready. People like these are the progressive ones. As the public has learned the cons of picture marriage in recent years, few women are willing to say yes when the men themselves do not come; when proposing through a picture, brides might fulfill only half of what men ask for in a bride. Women rarely choose to get married that way unless they look like they are from outer space or something.”

“Brides filling the ship gathered at the departure desk and looked at the crowd on the wharf, checking small pictures in their pockets. all seemingly at the same time….”As for the grooms who had come to… welcome their brides, they also looked in their pockets… This scene gave me such a sentiment which I could not quite explain. Some fainted as they faced each other and some grooms ran away… leaving the brides, who had crossed the 4,000-mile route of waves, alone there….

— Akatonbo Nakamura, “N Am Times” (1939)

“1,600 Picture Brides Landed in Seattle Last Year”

(NAT, July 28, 1919)

“According to a report of the Department of State, California Senator Ferguson (Hiram Johnson, R?) is ardently engaged in the anti-Japanese movement. The Japanese steamship Korea-maru brought another 150 picture brides there, in possible violation of the Gentlemen’s Agreement.

The Immigration Officer in Seattle, White, comments as follows: About 1,500 to 1,600 picture brides from Japan arrived in Seattle last year. They have all been through strict examination and have been permitted to enter, so this doesn’t violate the Gentlemen’s Agreement.”

To be continued

Editor’s note.

The Gentleman’s Agreement (1907-1908) blocked further emigration of Japanese laborers to the US, while still allowing wives, children and parents of current immigrants to emigrate. In exchange, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt would make San Francisco repeal its Japanese-American school segregation order.

Ikuo Shinmasu retired in 2015 from Air Liquide Japan Ltd., then researched his grandfather who migrated to Seattle. He shared his findings through the series, “Yoemon Shinmasu – My Grandfather’s Life in Seattle,” in the NAP and in “Discover Nikkei” in Japanese and English during 2019-2020. He lives in Zushi, Kanagawa, with his wife and son.

Mina Otsuka is a freelance translator for “Discover Nikkei.”