By Jonathan van Harmelen

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor and U.S. entry into the war, further commentary on Japanese American communities began to appear. An article published on December 18, 1941 in the fascist newspaper “L’Action Française” notes the presence of 100,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast (image in Nov. 26 issue). The article then further asserts that Japanese immigrants are unable to acquire citizenship or enter mixed-race marriages and are viewed with mistrust by Californian communities. The article concludes that U.S. authorities are constantly surveilling Japanese Americans, with particular attention given to communities like Terminal Island located near military installations.

“L’Action Francaise” followed soon after Pearl Harbor, on January 13, 1942, with another article on the Japanese American community. In addition to describing the laws created by the United States to ban immigrants from Asia, the article pointedly notes that the U.S., California in particular, is responsible for creating global race issues. As evidence, author J. Delebecque references the U.S.’s rejection of Japan’s proposed racial equality clause during the Versailles Treaty of 1919 and cites the work of writer André Duboscq, who notes that “the yellow question, simply of California origin, has become an international issue.” At the same time, the article pushes the notion of fifth-column activity among all Japanese communities throughout the Americas. In particular, the author notes the efforts made by Latin American countries, such as Brazil and Peru, to round up their Japanese communities and also, references efforts to imprison Japanese Panamanians as part of protecting the Panama Canal Zone.

An article on the Nisei by Claude Richemant appeared on January 7, 1942 in the Paris literary weekly “Candide.” Richemant noted that, even as West Coast whites accused Japanese Americans of disloyalty, many Japanese Americans took initiatives to support the United States. In addition to pointing to the adoption of American culture by Japanese American families and claiming (with some exaggeration) that there were thousands of Japanese American veterans of World War I, Richemant highlighted the work of the Japanese American Citizens League in encouraging members of the group to enlist in the U.S. Army.

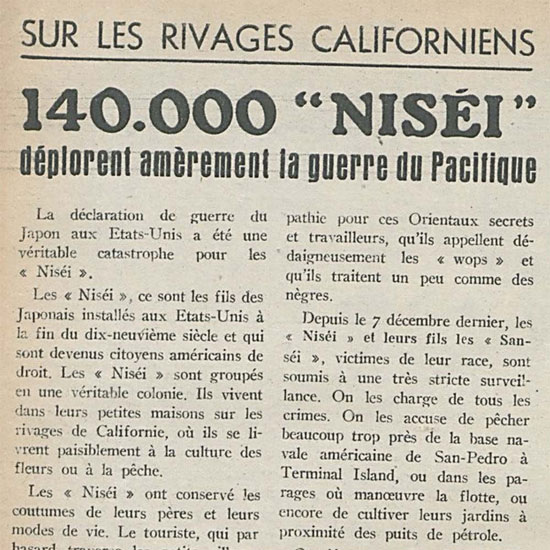

A similar article appeared meanwhile in the January 8, 1942 issue of the magazine “Marche.” Under the headline “On the Shores of California, 140,000 ‘Nisei’ Woefully Deplore the War in the Pacific,” the article notes that many Japanese Americans are angered by the start of the war, knowing that it will lead to persecution and general questioning of their loyalty. As with other stories, the article mentions the Terminal Island community and its proximity to the San Pedro Naval Base.

After the signing of Executive Order 9066 by President Roosevelt and the incarceration of Japanese Americans, very few articles appeared in French newspapers detailing the camps.

Although some news of the wartime incarceration spread to Axis-dominated states like France as a result of American media or nongovernment agencies such as the International Red Cross, mention of it in the collaborationist press were sparse indeed.

Conversely, in 1943, a newspaper in American-occupied Algiers reprinted an article by Swiss scholar Imre Ferenczi that documents the roundup and internment of Axis nationals in the United States. In contrast with Axis countries, Ferenczi describes the U.S. as having a “democratic” policy of imprisonment, noting the collaboration between the FBI and American citizens in identifying and arresting suspects. For Japanese Americans, the author notes their imprisonment in the “Far West” in states such as Arizona, North Dakota, and New Mexico, adding that the imprisonment of the Nisei was heavily protested by the American religious community. The author also noted that authorities exempted Koreans from confinement.

Occasional mentions continued to appear during the later years of the war, notably after the liberation of Paris in August 1944. On March 18, 1945, “Paris-Presse” featured an article about the city of San Francisco. Although dubbing it “one of the most beautiful cities in the world,” the article noted it as “a troubled city, where various races lived and where Japanese immigrants lived at one point until the start of war in 1941, when the United States sent the community to a number of concentration camps.”

Perhaps, the most detailed article to describe the camp experience for Japanese Americans is an October 20, 1945 article in the leftist literary newspaper “Les Lettres Françaises.” Written by Max Roth, the article traces the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment following the bombing of Pearl Harbor and through the incarceration. In Hawaii, a “crossroad of races in the Pacific,” Roth illustrates the hysteria of wartime Hawaii and California, noting how false rumors spread of sabotage, despite Japanese American soldiers fighting against the bombardment. In Hawaii, where mass incarceration did not occur, Roth points to the efforts by Japanese Americans on the island to prove their loyalty, such as serving in labor brigades despite their humiliating demobilization from the Army. Roth also includes a mention of the Ringle Report which stated that Japanese Americans remained loyal to the United States and that no acts of sabotage occurred. Conversely, Roth argues that the violence of West Coast whites and the inability of authorities to investigate loyalty led to the incarceration of the West Coast population and to its confinement in what he called “les camps de rassemblement,” or “reception centers” by the military. Roth also distinguished these camps from either the German death camps and French internment camps, noting the presence of better food and medical care.

Although Roth makes a number of incorrect arguments, his article is still most revealing in his statement that the confinement process deeply affected the Nisei and their ability to live in American society. Roth notes the distinguished war record of the Nisei soldiers in Italy, yet surprisingly does not mention their battles in France. (A picture of a Nisei soldier presenting a wreath for the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Paris would later appear in French newspapers in 1947). Although the war is over, Roth notes that West Coast whites continued their efforts to prevent the return of Japanese Americans.

It is worth noting that Roth’s article features two striking illustrations, one of which is from Miné Okubo’s “Citizen 13660.” (Okubo is never mentioned in the article, however, and a mention of “Citizen 13660” would not appear in print until 1950 in the “Revue Historique.”)

Source gallicabnffr Bibliothèque nationale de France

What can we learn from the rapportage of the Japanese American experience in wartime France? First, they highlight the incarceration as a topic of international interest even as it unfolded, with foreign observers commenting on the incarceration process. Second, the articles are revealing of French attitudes in their interpretation of the incarceration. No mentions, however, were made by French writers of their own wartime internment of the Japanese community of New Caledonia and interest in the topic has only appeared in March 2021 as part of discussions of the Japanese American wartime experience. In the case of French articles after the liberation, the story of the wartime incarceration underscored their interest in American definitions of citizenship and American racism, all of which would pass uninterrupted into the postwar years.

*For more information on European newspaper coverage of the incarceration, see Jonathan van Harmelen’s “Lessons from a Different Shore: Portrayals of Japanese American Incarceration and the Redress Movement by Western European Newspapers” in the Fall 2021 issue of the “Journal of Transnational American Studies.”

© 2021 Jonathan van Harmelen

Jonathan van Harmelen is a PhD student in history at UC Santa Cruz.

This article was originally published in discovernikkei.org, which is a project of the Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles.