Yoemon Shinmasu, Life of My Grandfather in Seattle

Vol.3 Marriage and family

by Ikuo Shinmasu, translated by Mina Otsuka

This is a series on the life of Yoemon Shinmasu, an Issei immigrant from a small fishing village in Yamaguchi Prefecture who made his barbershop business quite a success in Seattle, yet lost his life in an accident in his 40s. Yoemon’s grandson Ikuo was born and raised in Japan and has been always interested in Yoemon’s life in Seattle. He shares what he discovered through his research.

Continuing with the last part in which I wrote about Yoemon’s single life in Seattle, this part shares Yoemon’s marriage, children born in Seattle, and his barbershop business following the marriage.

Yoemon’s marriage and family life

In the early 1900s, the anti-Japanese movement became heated as hardworking Japanese immigrants increasingly impacted white workers. The Japanese government signed the Japan-US Gentlemen’s Agreement in 1908 to prohibit immigration from Japan to the US in order to alleviate the situation. This agreement made it extremely difficult for workers to travel to and from Japan freely; they had no choice but to give up on their original purpose of working away from home for a short time and bringing fortune home. Rather, they chose to settle in the US. Most of the immigrants back then were bachelors. Before the agreement, they used to go back to Japan to look for spouses once their life got on track. However after the agreement, as it was difficult to go back to Japan on a short stay, a great number of people started to bring “picture brides” – to choose spouses from pictures – to the US.

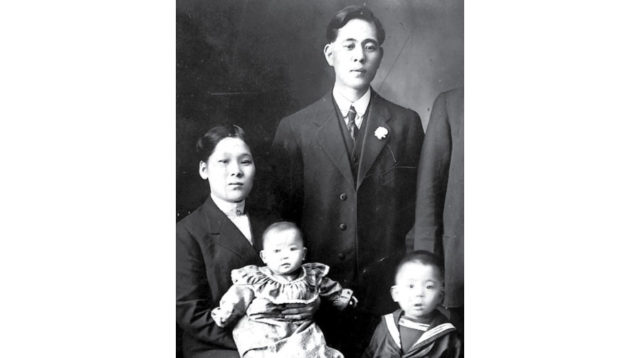

Yoemon also wanted to get married as his life in Seattle stablized. Some pictures of single ladies were sent to Yoemon from Kamai. Yoemon looked at one and immediately said, “She’s the one!” The woman in the picture was Aki Miyazaki from Kamai, his hometown. Aki was the eldest of five sisters, and she used to babysit her sisters when she was young. Aki’s brother was Yoemon’s friend who also had emigrated to Seattle. In truth, there were many troubles around the “picture marriages.” Many people found huge differences between how their brides or grooms looked in person and in the photographs. However, in Yoemon’s case, there was enough information to have trust in the system. After all, Aki was from his hometown and he knew her brother well. Yoemon thus got married to Aki in August 1911. Yoemon was 27, and Aki was 18.

The signature “C. Ito” on their marriage certificate was written by Chuzaburo Ito, who helped Yoemon start his barbershop business.

Now that he was married, Yoemon must have felt at ease after living alone in the US. In 1913, he called his younger brother over from Kamai to Seattle. According to the Kaminoseki-cho shi (History of Kaminoseki Village), his brother smuggled himself into the country. Yoemon waited on the shore near the port as the ship carrying his brother approached Seattle’s seaport. His brother secretly got on a small boat and landed. Later, Yoemon called another younger brother over to Seattle, in the same way again.

In September 1914, my father Atae, Yoemon’s eldest son, was born. His birth certificate was submitted from Seiichi Takahashi, the consul-general of Japan in Seattle, to Minister of Foreign Affairs in Japan Takaaki Kato. With his American birth certificate submitted as well, Atae became a Japanese American with dual citizenship. His American name was John Shinmasu. In 1916, the couple’s eldest daughter (my aunt who is 102 years old now) was born. Their second daughter was born in 1918, making them a family of five.

The Yoemon family rented a room in the New Central Hotel in Seattle’s Japantown. The hotel was run by Japanese from a place near Kamai. In those days, many Japanese people in Seattle were living in hotels. Ryunosuke Yoshida and his family, whom I introduced in last month’s issue as Yoemon’s barbershop business partner, were also living in a hotel, according to the book The Two Worlds of Jim Yoshida.

My aunt told me about their hotel life. “Since Yoemon’s two brothers came to the country undocumented, they ran a hog-raising business in a suburban area around Seattle while hiding themselves. They could have been sent back to Japan if the authorities had found them. At night, they sometimes swam in the sea to the hotel where the family was living and dried their wet clothes. We sometimes cooked hogs they brought from the farm and enjoyed pork dishes.” Though it was a small hotel room, for Yoemon it was a place where the family could spend their most peaceful moments together.

Couple’s barbershop business

Yoemon’s barbershop was located at 163 Washington Street, about a 15-minute walk from the New Central Hotel. I was able to confirm the locations of the hotel and the barbershop in the detailed map of Seattle’s Japantown in Kazuo Ito’s Hokubei hyakunen zakura (100-Year-Old Cherry Blossoms in North America). Aki trained to become a barber as soon as she arrived in Seattle. Her innate dexterity helped her quickly become a topnotch barber. It was the beginning of Yoemon and Aki’s couple barbershop business.

As I wrote earlier, most of the customers who came to Japanese barbershops in Seattle were not Japanese but Caucasian. This is how my aunt explained to me about the barbershop:

Their barbershop was in the basement, but the shop had bright lights. More than ten Caucasian regulars came to the shop daily to get a shave. My parents were not able to speak English at all, but the business was doing well. They worked their butts off from early in the morning until late at night. It’s amazing how much they worked.

Back in those days, it was a very common everyday routine for Caucasian people to go to barbershops for their daily shave. The service fee at barbarshops was separated into three parts: haircutting, face shaving, and neck shaving. These were priced 25 cents, 10 cents, and 5 cents, respectively as of 1916, according to reference documents. What attracted many Caucasians to Yoemon’s store was Aki’s shaving skills with her soft hands and dexterity. Compared to barbershops run by Caucasians where shaving was done by males, the service at the Japanese barbershop must have been comforting and thus allowed their business to thrive.

Japanese barbershops were lacking in financial resources that Caucasian barbershops had. Equipment was more compact, keeping upper class Caucasians away. But the Japanese barbershops could earn enough when they opened shops in appropriate places targeting middle class Caucasians and Japanese. The barbershop business was extremely promising for the Japanese. Yoemon started to dream of having a gorgeous barbershop like the ones owned by Caucasians.

Yoemon’s temporary return to Japan

In 1918, Yoemon made a temporary visit to Japan. It had been 14 years since he left Kamai. Yoemon, who had left Kamai wearing only what he had on, returned in a suit and tie. His father Jinzou was tearfully delighted to see his proud son. Having seen that his family was safe and sound, Yoemon returned to Seattle. All the villagers saw him off.

I found the records of his re-entry. Information such as the details of Yoemon’s family registration in Japan, his address in the US and his occupation in documents that were written in English with Japanese translations attached. The record says “Occupation: barbershop business. Scheduled date of sailing: November 29, 1918 from Yokohama Port. Ship name: Kamomaru.” At the end of this document was the name of his guarantor in the US, Chuzaburo Ito, whom I wrote about in detail in part 2. It shows the level of relationship that Yoemon had with Ito, who was the leader of the Japanese community in Seattle. Ito worked as chairman of the North American Japanese Committee for three years from 1921. Yoemon’s work and life was in large part supported by Ito. Yoemon had established a life in Seattle.

Yoemon returned to Seattle and his barbershop further thrived, with Aki working, too. However, there was one problem. Their three children would play around the shop, and though the couple loved them very much, the children had become a nuisance to their work. Aki talked to Yoemon and asked him what they should do with their children. Yoemon decided to take the children back to Japan and leave them with his parents in Kamai.

References

- Daijiro Yoshimura, Tobei Seigyou no tebiki (Guidance on Making Business Successful in America), Okajima-shoten, 1903.

- Edited by the Department of Historical Archives of Japanese Committee in America, Zaibei nihonjin-shi (History of Japanese People in America” Japanese Committee in America), 1940.

- Kazuo Ito, Hokubei hyakunen zakura (100-Year-Old Cherry Blossoms in North America), Nichibo Publisher, 1969

[Editor’s Note] : This series is a collaboration between The North American Post and Discover Nikkei (discovernikkei.org), which is a program of the Japanese American National Museum. It is an excerpt from “Studies on Immigrants in Seattle – Thoughts on Yoemon Shinmasu’s Successful Barbershop Business,” the writer’s graduation thesis submitted at the Distance Learning Division at the Nihon University as a history major and has been edited for this publication.