By David Yamaguchi, The North American Post

THIS IS MY 100TH COLUMN since Shihou Sasaki, former editor of the North American Post, deemed my prior occasional voluntary writing worthwhile enough to make it a regular feature of the paper, and started paying me as a freelancer to keep him supplied. That was in February 2016. Since then, we have armchair-traveled the world, plumbed the Japanese past, and surveyed films, books, and J-Pop culture. At this milepost, 70,000 words in, it is worth pausing to consider who cares and why I believe it matters.

WHO CARES? As I have written, to my knowledge, only a few of my sixty-something Japanese-American age peers read this paper. For most, it is simply “too Japanese” of a paper. I suppose this is to be expected, for we descend largely from families that have been separated from Japan since the 1924 cessation of the first wave of immigration from

Japan, now 95 years ago. By contrast, I find my readers—people who say they read these words when I meet them—among older JAs, age 70 and above, and among post-1968 Japanese expatriates. Perhaps the former, the older grandchildren of Issei immigrants,

demarcate the limits.

A smaller group of readers finds me online. These include visitors to Discover Nikkei, the online magazine of the Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles. DN gathers

and posts writing from the Japanese diaspora. Their readers include those in other parts of the US, in Brazil, and in Japan. About every seven months, DN emails to ask if they can repost one of my articles there. My columns there supplement those of Tamiko Nimura, their regular Tacoma writer, in providing views from the Pacific Northwest.

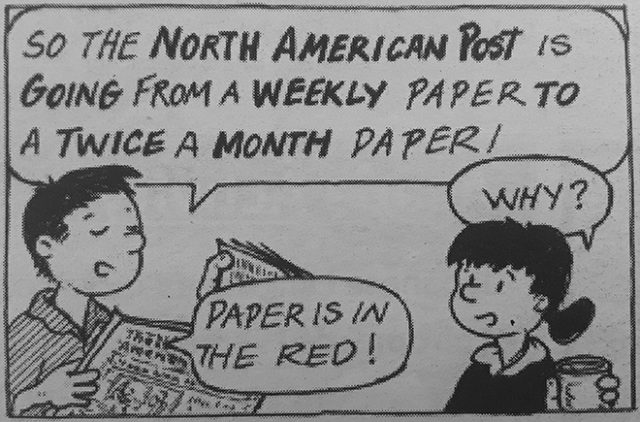

Beyond these generalities, I know only that 7500 print copies of this paper circulate twice a month to subscribers and distribution points—mainly Nikkei businesses—across Seattle and the Eastside.

WHY IT MATTERS. I think this column counts for something because I am one of about five regular, native-English writers who are each doing what we can to help keep a bilingual community paper alive. In doing so, we are maintaining a rare place where greater Seattle Nikkei can read in depth about their own experiences and community events. Without this paper, there are few other places where we can do so, or for Nikkei nonprofits to publicize their events. In short, we are harnessing these pages—setting them to work—while we have them.

One might argue that the local Nikkei landscape is already covered in English by the International Examiner and Northwest Asian Weekly. Yet I find that these Asian-American papers are so chockablock with news of the various immigrant groups that space devoted to JA/J content is necessarily sparse.

Second, with in the Nikkei community, I believe that I am helping to lessen the cultural divide between JAs and Japanese expatriates. Historically, the two groups have existed side by side, with only limited interaction, despite our shared roots.

Beyond documenting All Things Nikkei, I see these words as contributing to the written records of Sansei, together with Voices page-mate Deems Tsutakawa. As readers know, the stories of the first two mainland generations of JAs, from 1910-1920 immigration through World War II and 1980s JA Redress, have been extensively described. Yet, that flood of words fizzles to a trickle after that. Thus, the curious are hard-pressed to find

answers to questions like the following: Whatever became of JAs? What kinds of kids did the Nisei raise? What are JAs thinking about today?

I see our Sansei perspective as worthwhile because we are the most capable generation to date of expressing ourselves on paper in English and in other media. The flip side of this is that we are the first that is helpless on the streets of Japan.

Now 60 to 80, Sansei have also seen our fair share of history. We are the last to have known the Issei, our pioneering grandparents. We have watched Yonsei Millennials come into their own.

Accordingly, we are among the best positioned to understand and transmit our universal story of how immigrant communities evolve across four generations. Fourth, I am probably contributing—in a small way—to the ethnic awareness of self-selected working-age JAs. For us, without special effort, Japanese language and culture—beyond food—might as well come from Mars. Nonetheless, some understanding of these things is nonetheless expected of us by the internet-connected world today. Here, I believe this column provides a manageable way to get there. Whenever such readers shop at Uwajimaya, they can pick up a free copy of this paper. If they like this column, they can follow it online.

Lastly, I hope that I am something of a role model. I know that growing up in the 1970s, I regularly read the columns of Nisei writers Bill Hosokawa, based in Denver, and William Marutani, based in Philadelphia. I perused their sparse, inspiring words in Dad’s copies of the Pacific Citizen, the newspaper of the Japanese American Citizens League. In those days, there were few other places to read about JA life and concerns.

I remember admiring those men who came home from their day jobs, said hello to the wife and kids, and then sat down at their typewriters to crank out another column on everyday JA life for their faraway West Coast people. Both hailed from greater Seattle. From those insightful words, and from my parents, I gradually learned to see the beauty in the rhythms of an ordinary day.

WHY DO I DO IT? Like most writers, I compose for many reasons, but it is mainly out of love of words. While it is hard to say exactly when this crush began, I know that a key formative period was the early 1980s, when I was a forestry graduate student at the UW. In those days, I was in the forest for months on end. Thick books, beginning with ones I plucked off Dad’s shelves, became a way to pass quiet evenings off the electrical grid. Influential titles I remember reading by gas lantern included Hosokawa’s “Nisei, the Quiet

Americans,” and John Toland’s “The Rising Sun, The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945.”

I especially remember reading James Michener’s “Hawaii.” I carried a paperback version of it in my duffle bag on an expedition to the Brooks Range, northern Alaska. There, summers were commonly like Seattle winters.

There was one particularly miserable Alaskan night when every piece of clothing I had besides the one clean “tent set” I had on was soaking wet. I recall laying down thinking, “It better not rain again tomorrow, for what am I going to wear to work?”

Those nights could be especially uncomfortable because we were confined to our tents. A solid wall of mosquitoes awaited our emergence. Moreover, beyond the relative safety of camp—where three to four of us clustered around a shared shotgun—there could be grizzly bears. We feared drawing them from the surrounding landscape by our cooking, which frequently included freshly caught fish.

Accordingly, in the half-light of those arctic nights, we listened, like soldiers, for strange sounds. Yet for an hour each evening, until I fell asleep, I was warmed by a dazzling sun, as I paddled an outrigger canoe from Tahiti to the Hawaiian Islands.