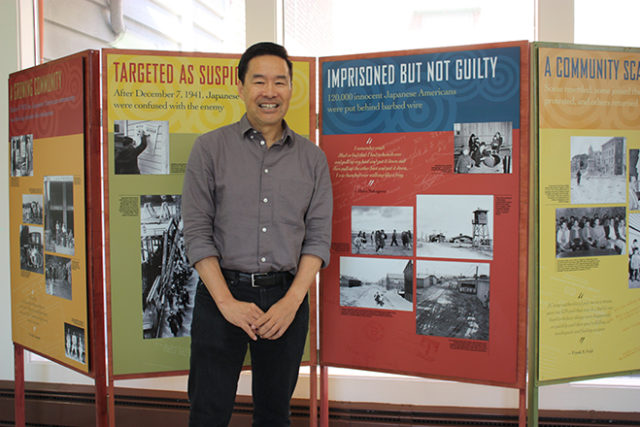

When Tom Ikeda set out to create Densho, a grassroots organization that preserves and shares oral histories and other material related to World War II imprisonment of Japanese and Japanese Americans, the former Microsoft employee and University of Washington grad thought he was looking at a three-to-five-year project. Twenty-two years later, he’s still at the helm, finding new challenges and making sure his organization will be ready to adapt to the artificial intelligence age. Ahead of the Densho Dinner gala at Meydenbauer Center on November 3, Ikeda sat down with the

North American Post to chat about his organization’s evolving role.

Interview by Bruce Rutledge

What is Densho’s role at this juncture in history?

Our role is to be that smart kid who does the research, thinks about it, and tries to find the relevance in ways that bring a better understanding. At Densho, because we understand the history of what happened to Japanese and Japanese Americans during World War II, we are in a really good position to highlight similiarities that we can learn from. We try to find what we call learning opportunities.

For example, during Trump’s campaign two years ago, he would say things that we found so alarming in that the rhetoric was so similar to what was used on Japanese and Japanese Americans in World War II. It’s what we call this “othering” of a group of people. “These people are dangerous. For national security reasons, we have to be careful and afraid of these people.” Way back then, we started raising flags. His followers and advisers would even say things like, “The Japanese incarceration thing wasn’t that bad. FDR was a good president and he must have had good reasons.”

Everything that had been determined and discussed and analyzed by historians started to shift two years ago. After President Trump was inaugurated, one of his first actions was this travel ban in predominantly Muslim countries. What we found interesting was this targeting of another group and otherizing them to make them seem dangerous. They said it’s a national security concern. We viewed it as a thin veil to hide religious discrimination in the same way they did to Japanese Americans. With the Japanese Americans, they said it was a military necessity to put them in camps. We know from looking at all the documents that there was no military necessity. It was just an excuse for racial discrimination against Japanese and Japanese Americans. When we see similarities, it’s our role to bring them to light.

Another issue that came up and seemed very similar to what happened to Japanese Americans was the family detention camps. There’s a quote, we can’t figure out who said it first, but I use it in my talks: History doesn’t always repeat itself, but it often rhymes. So, the detention facilities are different from the concentration camps in World War II, but again it’s the similarities. Even the separation of children. We use that as an opportunity

to talk about how in World War II, Japanese families were torn apart, in a different way – oftentimes, it was the fathers who were picked up by the FBI, leaving the wife and children to fend for themselves in very difficult situations.

In recent years, you’ve made an effort to reach out to other ethnic communities being vilified.

We went to CAIR Washington as well as MAPS (Muslim Association of Puget Sound) and asked, how can we help? There was this constant barrage associating them with being terrorists. During conversations with CARE Washington, it came up that a lot of the Muslim community is in the service. We reached out to Gold Star parent Khizr Muazzam Khan and invited him to Seattle. During the talk, I shared that my grandparents were Gold Star parents; my uncle was killed in action. Then Mr. Khan shared his story.

He spoke about how much the Muslim community appreciates how the Japanese Americans have stood with them. And the story of the Japanese Americans, the similarities and how much it resonates with them – he used it as a ray of hope. He said that as difficult as it is, to just know about the resilience of the Japanese American community was inspiring as a Muslim American. While we were there to support him, he thanked the Niseis in the audience, saying they were the heroes and how much he and other Muslims looked up to them.

The thing I love is that we walk into these situations thinking we know the history and can make connections, but once you do that with real people, we realize how much deeper and richer it gets. We are friends. We are connected. I feel like I know the Muslim community better.

That’s the powerful thing we’re trying to do more of: to not only make the informational connection, but to also start connecting with stories, and that means interacting more and more with these communities. That’s our evolution.

Your parents and grandparents were at Minidoka. Did they share stories of the War when you were growing up?

I grew up on Beacon Hill, then moved over to Genesee Park, so I was very much a working-class Rainier Valley kid. I spent hundreds of hours in the Nisei Veterans Memorial gym playing basketball. I did lots of sports. I was also a geeky kid. It really wasn’t until I got to Franklin High School that I understood more of what the camps were. In particular, there was one teacher in high school who was Japanese American and was in Tule Lake. She had me read the novel No No Boy. I asked my dad about the tensions between the World War II vets and the draft resistors. That opened up a really interesting conversation. My dad was a veteran, but he had many friends who went to Tule Lake or were draft resistors. He talked about how divisive that was for the community. My wife’s father was a draft resistor. Later on, I had long conversations with him about that. This was in the early ’80s.

What led you to form Densho?

Going back to my Rainier Valley roots, when I was at Microsoft, I got the chance to talk to Scott Oki. Scott is another Rainier Valley kid. When I met him, he was very high up, maybe the third or fourth highest executive at Microsoft. I was at a much lower level. We agreed that with our advantages working at Microsoft at the time, it would be important to do something for the community at some point.

Years later, after I had left Microsoft and after Scott had left, he called me and wanted to talk about doing an oral history project. I thought it was a strange project for someone who was once at a high level in Microsoft. But I met with him, and that’s when I found out about the Shoah Foundation. This was a project started by Stephen Spielberg after he did the movie Schindler’s List. They were videorecording oral histories. That was a new thing. They were also digitizing those videos, but back then they were using mainframe technology. When Scott and I went to Universal Studios where their offices were, they were jackhammering the streets outside their trailers because they were laying fiber-optic cable to get connected to the Museum of Tolerance and the US Holocaust Memorial. They were thinking point to point. That’s when it clicked for me. I said, “Scott, we can do this, and we can do it at probably a couple of orders of magnitude cheaper than the Shoah Project.” Their budget was $50-60 million. We could use personal-computer technology and connect to the Internet.

Did you realize how long you’d be doing this job?

I really thought this was going to be a three-to-five-year project. I was going to dive in, figure out the technology, do a couple hundred interviews, and be done. Twenty-two years later we’re still talking about all the things we want to do.

The first 20 years, we did Japanese and Japanese American history, but in many ways, I felt that we were siloed. But you almost have to start there. You have to really, really understand your topic.

You couldn’t have foreseen the rise of social media, so important to Densho, back in 1996.

We had a pretty good understanding that the world was going digital. At Microsoft, I worked in what we called multimedia publishing, which was essentially the old CD-ROM technology. What was clear to the people in that area was that everything was going to go digital. A big project I worked on was Encarta encyclopedias. I distinctly remember talking with people at Encyclopedia Britannica. They were making hundreds of millions of dollars

when we went there. We said we’d like to put your whole encyclopedia on a disc. It would cost us a few bucks for each one. Every year, we could send someone a new disc that is updated. You can search. It’s so much easier. They turned us down flat. They said, “We make so much money selling these print encyclopedias. We have tens of thousands of salespeople all around the country that go door to door. We have incredible distribution. Why would we support something that would cannibalize that?” Literally, within five years of that meeting, they declared bankruptcy. That’s how fast things were changing.

I recognized museums, newspapers, education; they were going to go digital. There were so many advantages. It wasn’t just about doing these interviews and digitizing them. It was about tagging them in ways and structuring them so that we could more easily find things and make connections. If you go to our website, any video or image that you find, you can also download. It’s an important productivity tool. That’s why filmmakers love us. They can search for, maybe, a woman who had children in camp, then they can click and download that file and put it into editing software and put it into their film. We can add context through tagging and other contextual tools. We were thinking about that sort of thing 22 years ago. We thought that by going down this path and thinking differently about how to organize this content, it would open doors.

And there is still more to be done. Even our platform is designed to be scalable. Right now, it’s the job of the archivist to put content in there. But we are thinking that within five years, we would want to do more crowdsourcing so that families that have photographs or documents could scan them at home and tag them in a way that makes them useful. We see information-sharing becoming more and more distributed than today.

The other thing that is huge – and people don’t really understand how much of a game-changer it is – is machine learning and artificial intelligence. We think that in five, 10 years, when someone does a search about an ancestor who was in the camps, rather than finding links to records, photographs, and newspaper articles, these machine-learning algorithms will have enough intelligence to think like a researcher. Then, with the thinking

of a filmmaker, they will put together a multimedia presentation that looks like it was done by a professional. And it will allow you to navigate. You could ask to go on the path of a family member as they left Seattle during the War. Then you could stop at the camp to hear more about that. It’s all possible because we have the content and it is tagged. Now we need the programs to be smart enough to pull it all together.

It’s a matter of making connections and telling stories to inform people?

Today it’s easier to make these connections online or in person. We spent 20 years collecting the information, organizing it. Today, we have younger people – artists and others – who can tap into that content much more quickly.

Tomorrow, I will have dinner with the CEO of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. She’s an African American woman, and she invited me to go speak down there. She asked me to speak on racism… in Birmingham! I did it. Before my talk, I walked through the museum. The amazing thing to me was how similar the stories were. They had their own black downtown, which in many ways was like Nihonmachi here. She told me that it was important for the people down South to understand that racism wasn’t just a black-white

thing. On the West Coast, it was more of an Asian-white thing. And now today, it’s more of a Latino-white thing. She said it really opened the eyes of the community to realize that it is much bigger than a black-white race thing.

“The thing I love is that we walk into these

situations thinking we know the history

and can make connections, but once you do

that with real people, we realize how much

deeper and richer it gets. “

About Densho

https://densho.org/

Densho is a nonprofit organization in Seattle started in 1996 to preserve the testimonies of Japanese Americans who were unjustly incarcerated during World War II. The organization offers these irreplaceable firsthand accounts, coupled with historical images and teacher resources, to explore principles of democracy and promote equal justice for all.

Tom Ikeda is the founding executive director of Densho. He is a sansei who was born and raised in Seattle. Tom’s parents and grandparents were incarcerated during World War II at Minidoka. Prior to working at Densho, Tom was a general manager at Microsoft Corp. in the Multimedia Publishing Group. Tom also worked as a research engineer developing hemodializers (artificial kidneys) with Cordis Dow Corp. and as a financial analyst at the Weyerhaeuser Co. Tom graduated from the University of Washington with a BS in chemical engineering, a BA in chemistry and an MBA.