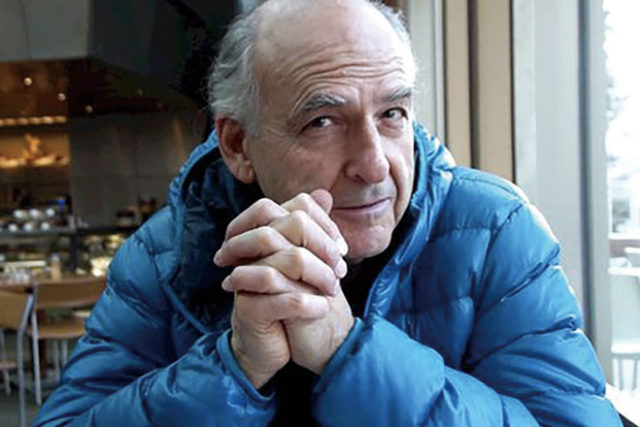

Jay Rubin is best known for his translations of Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami, but the former University of Washington and Harvard professor has a seemingly insatiable curiosity that has kept him extremely busy since he retired from teaching in 2006. Most recently, Rubin is putting the finishing touches on an anthology of modern Japanese stories, to be published by Penguin with an introduction by Murakami. Seattle area residents may also be familiar with his debut novel, The Sun Gods, which came out in 2015. In it, Rubin depicted with fiery passion the injustices of World War II, when 120,000 people were imprisoned for being of Japanese descent. The novel is set in Seattle, Minidoka and Japan. The North American Post caught up with Rubin at his Bellevue home. Excerpts from the conversation follow.

Interview was conducted by Bruce Rutledge

NAP: Tell me about this anthology you’ve been working on for Penguin.

Jay: I’m not putting it together like the usual chronological anthology of stories from early Meiji to contemporary times. Instead, I’m putting the stories into thematic categories. There’s one called “Japan and the West,” with writers like Nagai Kafu and Soseki (Natsume), who are writing deliberately about Japan’s relationship with the West. That’s one section. There’s another section called “Men and Women,” which are stories about relations between the sexes. Another section is called “Modern Life and Other Nonsense,” with humorous stories. I am putting it together with stories that are related in terms of tone and mood. The only section that is chronological, not by publication of the stories but rather by the events, is the “Disasters Natural and Manmade” section. I start with the 1923 earthquake, and then things connected with the War. I have a story about Hiroshima and a wonderful story from Nagasaki Ground Zero, a book that came out from Columbia University Press. There’s wartime, then postwar, and the last section is connected to the Fukushima disaster.

There’s a beautiful story of (Yasunari) Kawabata’s in the postwar section. Then there’s a story I did a long time ago for another anthology, “American Hijiki.” Do you remember the book Contemporary Japanese Literature, edited by Howard Hibbett? That was a great book. I had two pieces in that, including American Hijiki by Nosaka Akiyuki about a guy who goes through wartime as a teenager, then works as a pimp. His wife invites some Americans to come visit them 20 years later, and he’s torn by this whole thing, remembering his experiences during the war and trying to be indifferent about the fact that these Americans are coming to their house. He completely relapses and becomes a pimp again! (laughs) It’s a very funny and sad story, a wonderful story. I was really glad that I could use that.

I have edited all the stories. That was the hard thing. I went through everything line by line and found a whole lot of stuff that I wanted to fix in other people’s translations and my own too!

NAP: When is it coming out?

Jay: About a year from now. I can say that at last. It was supposed to have come out three years ago. Last November, December I finally got into the editorial phase. I enjoyed that tremendously. I had never done anything quite like that before.

The last part for me to work on will be translating Murakami’s introduction to the book. That’s how I’ve mostly worked with him over the last few years. He did an introduction to my Akutagawa book (Rashomon and 17 Other Stories, Penguin 2006), and he did another for my re-translation of Sanshiro by Soseki (Penguin, 2010), and another for my translation of The Miner (Soseki, Aardvark Bureau, 2016). He did all three. They are wonderful. I was surprised he agreed to do this newest anthology because it would require him to read contemporary writers. He’s been good about reading the classics — Akutagawa and Soseki — but I didn’t know if he would take this on.

The anthology includes a section on disasters. Could you tell us more about that?

I went through a period where I probably half consciously avoided anything about the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I kind of forced myself to start. I read a whole lot of stuff in Japanese about both bombings. There’s a whole genre of Japanese literature called genbaku bungaku (A-bomb lit). I got particularly interested in a writer called Ota Yoko who was one of the more successful professional writers (in the genre). I’m excerpting a fairly long chapter from her book called “Town of Corpses” for the anthology. It’s really horrendous.

NAP: Reminds me of Buddhist art featuring these wretched demons.

Jay: Yeah, like hell screens. That was tough to write. You have to imagine all that stuff to put it on paper. It’s pretty grotesque.

I went through this period of reading a lot of genbaku bungaku. If I hadn’t done that, I wouldn’t have been able to write that Nagasaki chapter in The Sun Gods (at the end of the novel).

NAP: Speaking of The Sun Gods, this summer you went to the Powell Street Festival in Vancouver, BC, and you told me earlier that you learned quite a bit about the Canadian internment. What did you learn?

Jay: I didn’t know much about it until I was put on a panel with Joy Kogawa. I figured we’d both be interviewed as novelists who wrote about the internment, so I better know what she wrote. I read her most famous book, Obasan. I read three books of hers before the panel because I got really interested. I really enjoyed Gently to Nagasaki. In fact, I’ve read it twice now.

The main things about the Canadian case that were so different from the American case is that the Canadian government itself confiscated the people’s property. We didn’t do that to people. We just locked them up behind barbed wire and aimed machine guns at them. It comes across in The Sun Gods in that scene where people are selling their stuff for a pittance before they have to go to Minidoka. There’s that scene where the woman smashes her own pottery rather than take the few cents that she’s offered for it. But at least the government didn’t confiscate her pottery. The Canadian government confiscated people’s houses and cars and businesses. It was just astounding! They sold this property to pay for the program. Here we are, we’re going to lock you up and we’re going to sell all your goods, your homes, your businesses to pay for what we are going to do to you.

Also, it shocked me to learn that people were imprisoned until 1949.

That’s the other thing. They called it repatriation and dispersal or something like that. It’s just what it sounded like. They gave everybody a choice to go back to Japan, and most people hadn’t been to Japan. They had no real Japanese ties.

One big difference between the American and Canadian internment was the numbers involved. The US locked up 120,000 people. The Canadians locked up 21 or 22,000. The US program was a much bigger thing. With the Canadians, about 4,000 agreed to return to Japan … I should say go to Japan. In The Sun Gods you see people choosing to be repatriated by taking the Gripsholm, that big Swedish ship, back to Japan. In the Canadian case, they worked it out as a postwar thing and negotiated with the Japanese government, and something like 4,000 people got sent to Japan. I don’t know what happened to them, how successful their repatriation was or how many suicides were involved. They repatriated 4,000 and the rest they scattered all over the country, deliberately breaking up communities, preventing the Japanese from forming communities. We didn’t do that. It was really ugly.

Q: What books you would recommend about the American internment?

Jay: Infamy (Richard Reeves, Holt, 2015) which I never fail to talk about. It came out a month before The Sun Gods. In this area, you’d have to read Nisei Daughter (Monica Sone, 1953, Little Brown). No No Boy just got re-translated (into Japanese). That’s an important book to read. Farewell to Manzanar. Desert Exile. I learned about how they would lock people up in stables. They would whitewash the stables, and there would still be flies under the whitewash. They hadn’t cleaned them up, just whitewashed them.

The point of The Sun Gods was to not give yet another factual memoir, but to try to get some emotion in there.

Is there a raised awareness of Japanese American issues in Japan these days?

Somewhat. I think The Sun Gods did what I was hoping it would do in this country. It was more widely read there. That helped a little bit. There is a young guy called Fujii Hikaru, a professor at Doshisha, whose specialty is Nikkei bungaku (ethnic Japanese literature). At this point, he’s looking into the possibility of getting a translation of Joy Kogawa’s Gently to Nagasaki.

Q: Why did you start studying Japanese?

Jay: It could have been Chinese or Chinese history. It was my second year of college (at the University of Chicago). I was planning to start majoring in English the following year. Or philosophy. I hadn’t made up my mind. I figured that once I chose my major, I wouldn’t have time to do any unusual course, so I ought to take something non-Western. And it just so happened that that quarter, there was a Chinese history course, but somehow, Japanese literature sounded better. The professor would bring both the English book that we were reading and the original Japanese book to class. He would talk about the translation, and he would talk about how much better it would be if you could read it in the original. That summer, I bought the textbooks they were using at the University of Chicago, started studying Japanese, and I was hooked. I ended up majoring in Far Eastern languages. They gave me the B.A., and I figured I needed to go to graduate school to learn something!

There’s a scene in The Sun Gods where Bill meets this old guy who’s dressed like a Meiji character. I met this guy. It was near Yotsuya Station. There’s a green berm there, a park. I was walking around there, and I met this man who looked like he was from the Meiji Period. He said, “Hey mister, you from the States?” He used to sell popcorn on Coney Island!

NAP: What do you do when you’re not translating and writing?

Jay: I saw Allegiance (George Takei’s musical about the internment). It is really worth seeing. It was really well done. I liked it enough to see it a second time. It was at the Lincoln Square Cinema. There’s a company that puts on opera broadcasts there. We’ve been to lots of operas. They have live broadcasts from the Metropolitan Opera. You’re actually watching a live opera. It’s beautifully done. It’s astounding to me that the directors are so good. They know just where to aim their cameras. Occasionally a camera will snap into focus after being out of focus and it reminds you that this is happening right now.

NAP: I also heard that you go back to Japan in the fall each year for a guitar jam session with translator Motoyuki Shibata and other friends. Is that true?

Jay: A lot of times, people have asked me, why are you going to Japan? Are you going to be doing research on this or that, and the answer is, I’m going to have a guitar jam with Motoyuki Shibata!

Jay Rubin is one of the foremost English-language translators of Japanese literature. He is best known for his numerous translations of works by Haruki Murakami, Japan’s leading contemporary novelist. Rubin’s novel The Sun Gods was published in 2015. He taught at the University of Washington and Harvard University until retirement in 2006. He lives in Bellevue with his wife.

The Sun Gods by Jay Rubin Rubin’s debut novel, published in 2015 by Chin Music Press, is set in Seattle, Minidoka and Japan.

Sanshiro (Penguin Classics) by Natsume Soseki Translation by Jay Rubin and Introduction by Haruki Murakami Rubin’s recent re-translation of the Soseki classic Sanshiro contains an introduction by Murakami.